Solving the riddle

Two years into my PhD and with nothing to show for it, a failing side project (of all things) provided the clue that would bring clarity. Slowly, but surely, a harsh truth emerged.

The Covid project came at a pivotal time of my PhD. I had chased a seemingly unsolvable problem for two years, and was accordingly tired. Something needed to give. I had depleted the resources at my disposal and was running out of options. The chance to redirect my attention was thus a sliver of hope. Perhaps I would be able to finish my degree after all. But once again, I found no signal and the situation quickly felt all too familiar.

However, this new experiment diverged from the main project in one crucial aspect: The specimen was limited and used by the entire lab, meaning the various investigations needed coordination. So while my colleagues were busy collecting and processing data, I was left waiting for a new sample to be used. Additionally, this time, there was no need to verify the specimen’s integrity. The successful measurements of my colleagues were proof enough, and with no troubleshooting to plan, I suddenly had a lot of downtime.

Not having much to do, I spent my day reviewing literature and eventually realised a peculiar thing. Despite decades of scientific interest, the targeted interaction type had never been directly observed. Apparently, the only person to ever do so, was my predecessor—but the gravity of their achievement was nowhere mentioned. Neither in their articles nor their thesis. In fact, they never highlighted the type of interaction, nor even acknowledged that it was difficult to resolve—an entirely surprising omission, as accomplishments of this kind are usually shouted from rooftops. Science is highly competitive, and nothing procures more reputation—or funding—than succeeding where others fail.

With the literature research raising questions about the experiment’s feasibility, it was clearly time to scrutinise my predecessor’s findings, but their data was nowhere to be found. The respective hard drive had been lost before I joined the lab, and the original results were no longer on the measurement device—despite ample storage space and even older data still available. Of course, the department was aware of the loss, and attempts of retrieving the information had been ongoing throughout my employment. Unfortunately, all unsuccessful.

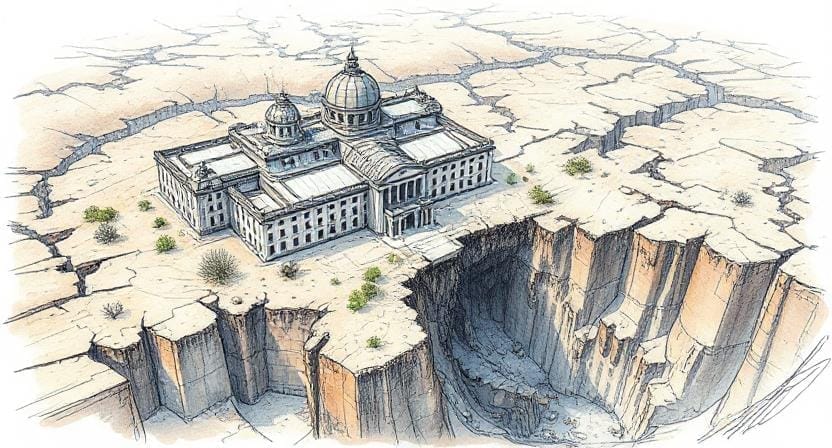

This circumstance had already caused significant friction between my supervisor and me. I had insisted for some time that the previous findings had to be dismissed, since proof was no longer available. My supervisor countered that the data had been collected, processed, and discussed within the department over years, and could be trusted despite the loss. With none of us yielding position, the debate frequently turned uncomfortable.

The literature review strongly solidified my doubts and ultimately tipped the scales. When I first joined the project, I was out of my element and trusted the institute with its findings, not least because of my supervisor’s three decades of experience. The department specialised on interaction measurements, and with results already collected, there was no reason to question my project’s viability. By now, I had invested a couple of years and found so much conflicting evidence, it simply outweighed any benefit of the doubt.

I thus reviewed my predecessor’s thesis once more, with intensified scrutiny and a slightly shifted focus. This time, I didn’t look for details that would explain my failing, but theirs—and it finally clicked.

There was a simple explanation for everything, and it had been right in front of me: My predecessor had mistaken an artefact for a signal. The entire project was built on faulty data.