Questioning knowledge

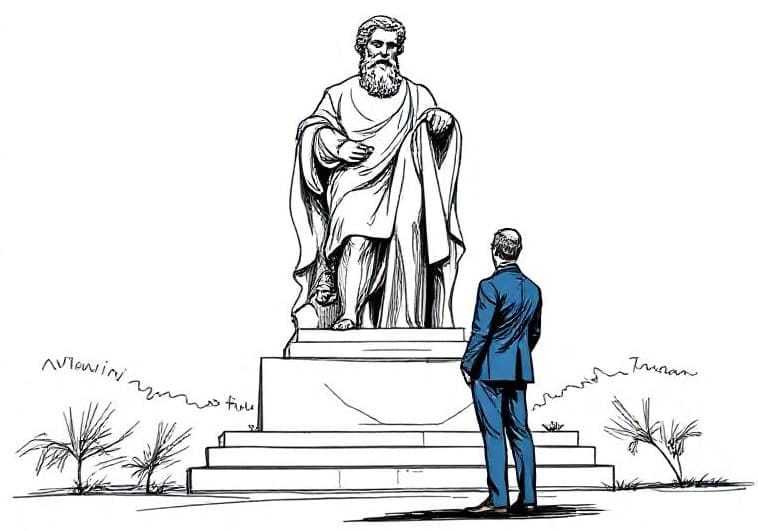

As one of theoretical philosophy's core areas, epistemology concerns the notion of knowledge. Even Plato contemplated the difference between knowing and conviction, and formulated a definition that would remain relevant for more than two millennia.

To him, three conditions had to be met: (1) a subject S must be convinced of p, which (2) is indeed the case, thus true, and (3) S must have a justification for the conviction p.

These conditions are individually necessary, meaning knowledge cannot exist without any of them, whereas taken together, they form the sufficient condition for knowledge—if all three conditions are met, S must have knowledge of p. This classical understanding of knowledge as justified true belief was only "recently" challenged, when Edmund Gettier (in 1963) proposed examples in which the subject failed to attain knowledge, despite being justified in a true belief.

In these scenarios, Gettier essentially describes situations of epistemic luck, where a warranted justification from an erroneous assumption supports a factually true conclusion by happenstance. The subject is thus justifiably convinced of a true circumstance, but clearly fails to attain knowledge.

An example:

Person X observes person A as they leave X's building. Person A carries the exact same television that X owns. Upon entering their flat, X realises their TV was stolen, and concludes that A took it. And that is factually true; A did indeed steal the TV—but X never saw it. Instead, the saw A's twin, person B, who just happened to be carrying a TV. The real theft was unobserved, and took place ages ago. Thus, X is justified in a true belief, but the situation does not constitute knowledge.

Gettier's brief, but influential essay provoked a comprehensive, ongoing debate about what else is required to actually speak of knowledge. While Plato's first two conditions (conviction and truth) are generally uncontested, what justifies knowledge is hotly discussed. Some approaches focus on the subject, demanding an ability to discriminate potential alternatives from p (e.g. to discern the twins in the above example). But that depends on the situation and doesn't really enable any global definition. Others find the culprit in the generation of knowledge, but are faced by the same problem. The method by which knowledge is created is highly situational, can be more or less reliable, and may well yield true conclusions accidentally (e.g. when looking out the window at the exact right moment to observe something).

Even beyond that, is justification truly necessary? If someone loses trust in one because they get confused, do they necessarily lose their claim to knowledge? For example, if I know Caesar was stabbed, but someone convinces me he was poisoned, do I still know he was murdered? It is not easy to resolve such issues…

It does stand out, however, that all these approaches implicitly assume knowledge can indeed be defined regardless of situational circumstances. Contextualism disagrees with this assumption. As its name suggests, it views knowledge as context-dependent, which opens up room for circumstantially reliable methods, or different states of knowledge within unchanging circumstances (e.g. whether a room is known as clean depends on whether it houses a sterile laboratory, or a bathroom). But in that interpretation, knowledge no longer constitutes a verifiable fact. Instead, it becomes relative to either the situation, or the person allocating it—contrary to all intuition.

In sum, it appears we can't really say what knowledge ultimately is. The term is still surprisingly contentious, and while it seems clear to entail some things, it is unclear what defines it conclusively. Considering the rich debate and its many generated examples, it is entirely possible that there is no final answer, but that knowledge means different things at different times.

This article summarises my understanding of the introductory part of:

[1] J. Hübner, Einführung in die theoretische Philosophie. Stuttgart: Verlag J.B. Metzler, 2015.