Philosophy of Nature (Ancient Greece)

Curiosity seems to be one of humanity’s most important traits. It underlies focus, interest and insight, and thus forms the soil of creativity.

It is thus unsurprising that humanity has questioned things throughout history; a process that has culminated in science as we know it today. But despite this impressive progress, some answers remain elusive still.

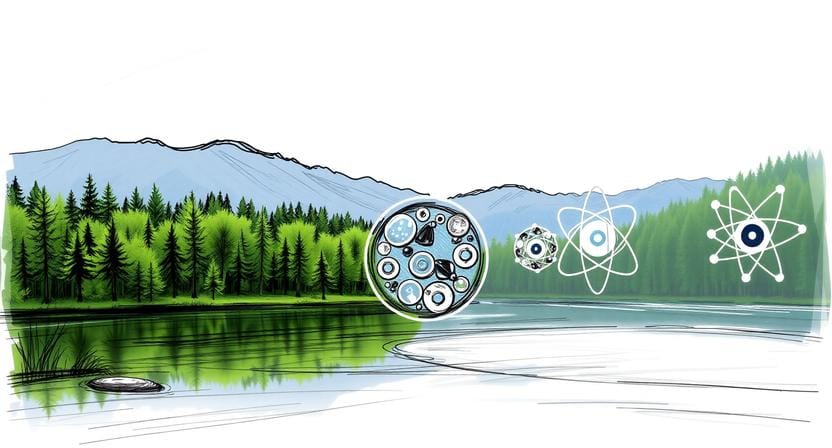

At the heart of these questions lie nature and its mysterious makings. Some of the earliest surviving writings go back two and a half millennia, to the Presocratics. These earliest (Western) philosophers interpreted their surroundings as the unfolding of somewhat intrinsic principles. Like a flower that sprouts, the world grows not in arbitrary ways, but in an ordered, structured fashion.

Importantly, the Presocratics didn’t just attribute their observations to obscure forces or deities, but sought to explain them through nature itself. They thus set out to find nature’s primal substance, but quickly ran into problems with their interpretation. Considering all matter one and the same thing doesn’t really clarify much. In fact, it makes it difficult to grasp why (or how) the various elements of nature interact with one another (in so many ways). Consequently, philosophers expanded their ideas by adding various aspects (like mathematics, for example). Bit by bit, the model grew, slowly making place for more elements, interaction forces, and even atomistic conceptions. One step at a time, our view of nature became ever more mechanical—a view that raises a difficult question: If nature is mechanical, it doesn’t move by itself. So what caused the first movement?

A few centuries later, Plato was dissatisfied with this materialistic focus. Impressed by the beauty of nature, he reasoned it would be impossible for such complexity to occur by sheer happenstance. In his mind, the world was an artwork, the masterpiece of a godlike artist. While Plato can indeed be considered the first monotheist, his conception differs from more modern myths of creation in key aspects. His “god” is a craftsman, not the universe’s original creator; a demiurge who may have sculpted the world, but he did so with existing material—and after ideas that lie beyond him, still. Plato’s physical world exists only against this backdrop of metaphysical, perfect ideas.

His student, Aristotle, then returns to more empirical views and divided the field in two: first philosophy (later termed metaphysics) and physics. Aristotle thus drew a line between the principles that enable existence in the first place, and the matter that does indeed exist. Trying to understand how reality behaves, he made a number of intriguing observations, for example that things behave not just according to substance, but shape as well. In fact, an object’s shape is what ultimately brings out the material’s quality! (Wheels roll because they’re round, not because they’re wooden, after all.) He also distinguished four different types of causality: Things are not only determined by substance and shape, but also a cause (as we understand the word today), and a final destination. These various dimensions of an object cannot be reduced any further, as each aspect yields a distinct, but valid, reply to the question “Why?”: A house is made of wood and stone (cause materialis), has a more or less defined shape (causa formalis), is built by people (causa efficiens), and serves to protect its inhabitants (causa finalis)[1]. Despite Aristotle’s understanding of cause and destination, he rejected the need for a godlike intelligence: What produced existence in the first place is not a physical question, but the topic of another discipline. Nature, to him, was mechanistic, indeed.

Almost two thousand years later, this mechanical view of the world grew even more convincing, as the clock’s development proved the potential of mechanical systems. Meanwhile, mathematical advances explained ever more phenomena. Slowly, but surely, the need for supernatural forces vanished, paving the way for what would become modern science.

It warrants mentioning that Aristotle’s understanding of “purpose” (telos or causa finalis) is not limited to human intention. It is better understood as an object’s resting state or natural end (e.g. a ball that comes to rest in a valley). ↩︎

Note that this is not a conclusive, or even necessarily correct interpretation. It is merely an attempt at summarising a bit of learning material.