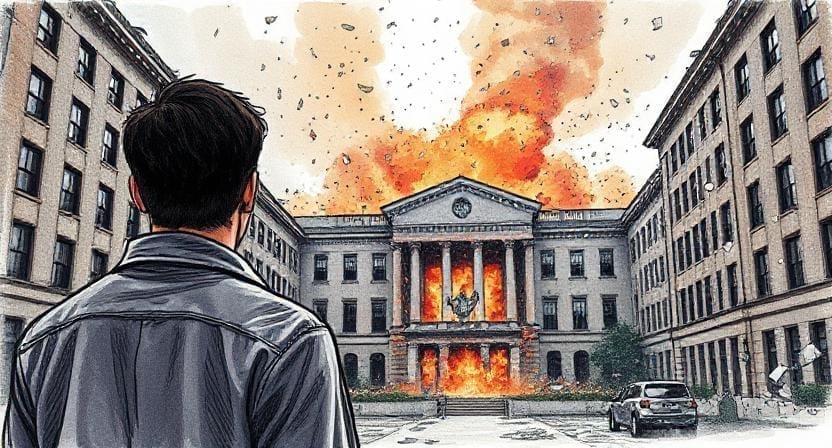

Lighting the fuse

With my supervisor denying an uncomfortable truth, I was locked in place until I finally burned out. I nonetheless persisted, uncovered a smoking gun—and fired the first shot.

For two years, I had spent all my energy on trying to understand what caused my PhD project’s deadlock. So when I finally found the answer, I was expecting things to improve. Sure, the problem was much larger than anticipated, and the entire project needed a full reset, but at least now we could move on. Unfortunately, my supervisor disagreed.

At the time, three different students had failed to replicate any of my predecessor’s results (for a cumulative seven years of effort). Between that, the numerous troubleshooting experiments, the literature review, and the loss of the project-foundational data, the flaws I had found in the (extremely sparse) results of the predecessor’s thesis seemed like the last nail in the coffin. But my supervisor still refused to acknowledge the reality of the situation.

They argued that my newly voiced criticism was irrelevant because it targeted only graphs and plots that exemplified the process of data analysis “and not real results”—but that’s all there was. The entire thesis shows nothing else in detail, and neither do the published articles on the same results. Somehow, what sufficed to uphold the validity of all my predecessor’s findings and warranted their doctoral title, was impertinent when questioned.

In general, the absence of information emerged as a recurring conundrum: the type of interaction had never been resolved, my predecessor’s data was gone, their publications were eerily devoid of actual findings, and my own measurements returned no signal. So, while I suddenly found myself opposing everything around me, I could produce no concrete evidence at all. At first, this seems to weaken my position, but the expectation of proof is actually misplaced. Evidence must be provided by whoever makes a claim. In this case, my predecessor.

For a while, I tried to get through to my supervisor, but they didn’t want to hear it. No matter what line of argument I launched, everything was brushed aside without consideration. I had no more room to move and finally burned out. It took me weeks before I could return to work.

When I did, I generated an update report in hopes of finally swaying my supervisor. It listed all the different troubleshooting experiments, highlighted how everything except the main approach worked perfectly, and gently, carefully mentioned that it may be time to look for new avenues of investigation. Perhaps the instrument simply could not achieve the necessary resolution. My supervisor replied that I should continue unchanged. This time, it would take several months before I could return to work.

By the time I got back, I had reached two conclusions. One, nothing would ever suffice to convince my supervisor, and two, I had gone far beyond my breaking point too often; this was my last shot. It was subsequently relieving when I was instructed to shift my focus temporarily. The new experiment followed another predecessor’s protocol and targeted a different type of interaction. At long last, a bit of hope again—coupled with caution.

If anything, the past few years had revealed that not all the department’s findings could be trusted, and I used that knowledge to buffer against disappointment. At first, I was optimistic. The measurement was simpler and the interaction less obscure. But the closer I looked, the more wary I grew. The relevant thesis showed the exact same issues I had already encountered.

Unsurprisingly, the experiment returned no signal.

This time, I didn’t search for errors in my approach, but immediately scoured the lab for the raw data. My chances were slim, as these findings were even older than my main project’s lost results, but to my surprise, I found them. They were still on the instrument, and proved exactly what I had predicted by the flaws in the theses: The experimenters had used inappropriate measurement parameters, introduced an artefact, and then mistaken it for a signal. None of it was real.

I went straight to my supervisor, told them forthrightly what I had found, and urged them to come see for themself. They instantly denied such a grave mistake would ever occur in their lab, let alone remain undiscovered for so long. With a shaking head and pity in their eyes, it was clear they had given up on me. They never even looked at the data.

From their perspective, the situation was clear and the only problem was I: A newcomer that couldn’t find into the field, failed to get ahead, burned out in frustration, and began lashing out at everything around them. A much more comfortable narrative than my alternative, which saw them failing in spectacular fashion. In my version, at least two employees had failed to understand the measurement technique’s basic fundamentals, and the lab’s entire staff didn’t realise for years. It would mean my supervisor was asleep at the wheel for a significant period. If true, it would cast serious doubts on the institute, if not the entire university, and would likely necessitate the withdrawal of several articles, and possibly even doctoral degrees.

But none of it mattered any more. The future was determined, our trajectories were set. Confrontation was inevitable. I had tried what I could to solve the issue internally, but clearly that wasn’t happening, and there was no way to find support. The next contact person would have been my supervisor’s boss, but there was none. They were head of the department, head of the institute, and head of the doctoral college, all rolled into one. I also couldn’t expose my findings to anyone outside the institute; these insights in the wrong hands could cause serious damage. And contacting my university’s ombudsman seemed inappropriate, too. No matter what options I weighed, they all felt tantamount to backstabbing.

I only saw one way forward. The doctoral college’s next assembly was rapidly approaching, and I was scheduled to present my project’s progression. In my mind, outlining the situation within that setting was the least destructive path. I would expose a harsh truth and attack my own department, but at least within narrow bounds and not behind anyone’s back. I wouldn’t break confidentiality, as the project was part of the doctoral college, and I would bring in a group of experts, all of whom knew the experiment’s basics from watching on the sidelines. Even if my supervisor would remain the subject authority, the college’s combined expertise could surely help clarify which of us was right—and clarity was all I wanted.

So, during the next general assembly, I let slip the dogs of war.