Institutionalised inertia

In growing need of clarity, I finally reached out for help, unaware the step would only mark the beginning of a surreal and taxing journey.

Going to the ombudsperson proved difficult. I had honestly tried to avoid bringing them in; it felt like an unnecessary escalation, tantamount to betrayal. But half a year after my dismissal, I still was none the wiser. No one had ever actually responded to my data criticism, and the uncertainty was driving me nuts. The problem had been so elusive for so long, it had made me doubt my mind for a while. After all, I was going against decades of experience, in a field outside my expertise. Fully aware of what cruel distortions a stressed mind can produce, it seemed entirely possible that I was simply wrong. Not knowing whether I could trust my reasoning was simply too much, and to figure it out, I needed help.

The first meeting took a lot longer than anticipated, and it struck me as odd that my counterpart took notes in pencil, of all things. They scribbled away as I went on and on. Even without the field-specific stuff, they filled several pages, and by the end of it, we were all tired. I left with dampened hope. Apparently, things like this usually don’t go over well. Most of what I had reported wasn’t directly actionable and either difficult or impossible to prove, so even if I could force a board investigation, my chances were slim. And even if I was found to be right, the repercussions would be small. A slap on the wrist—maybe. By the ombudsperson’s best judgment, if I wanted to pursue this further, the best place to go was the university’s second ombudsman—specifically responsible “to safeguard good scientific practice”.

I was of course aware such a department existed, but never reached out for one simple reason: one of its board members was also a doctoral college faculty member—and thus already knew, yet never bothered acting. Even worse, despite their position, they never reached out for just so much as a conversation, not even after my talk. If anything, informing that department seemed risky, but I was out of options. So, finally, I messaged the two contacts suggested by the (student’s) ombudsman, hoping against reason it wouldn’t come back to bite me.

The chairperson responded within half an hour: They no longer held that office, and hadn’t done so for one and a half years. The second contact—and dean of my faculty—never answered. They weren’t on campus when I called, and despite their secretary assuring me to the contrary, never replied to my e-mail. Ten days later, I wrote another one that was equally ignored. No out-of-office message, nothing. Both contacts would remain listed in their supposed function as ombudsman for at least another half year. Little did I know that my Kafkaesque journey was only just beginning.

The absurdity was exhausting, but it ignited something in me. This was a scientific institution, after all. It was subscribed to the protection of truth, and by now, the situation was simply too large. It was no longer about one project’s problematic results. That much could be brushed aside as an innocent error. But now, this was about much more: A decade of neglect, unreliable measurements in at least two projects, an entire department not recognising obviously flawed data, dozens of scientists (across three different universities) refusing to do anything when informed of the misconduct, and now two ombudsman departments failing their duty—not to mention the financial damage, or the impact on career chances, health, and the sanity of more than one person. No, this wouldn’t do.

There was only one more possible contact, and it meant a shift in gear. If I was going to reach out to the country’s highest authority on scientific integrity, I would need to prepare. There was no more room for uncertainty, only concrete proof and delicate awareness of the accusations I would forward. This was escalation, but, under the circumstances, it was absolutely justified.

I actually had to trick myself into the work. I was still reeling from the burnout, scared absolutely shitless, and acutely aware of just how unreliable stressed brains can be. What if I was wrong? What if my mind had conjured up an explanation just to survive? I would have to live knowing I couldn’t trust my perception—and things were frequently so absurd, it was hard to believe they actually happened. So, I told myself this was just for me. Should I turn out wrong, my case be too weak, or my strength fade before I could finish, I could always put things aside. I wouldn’t have to send it anywhere; this was only about clarity.

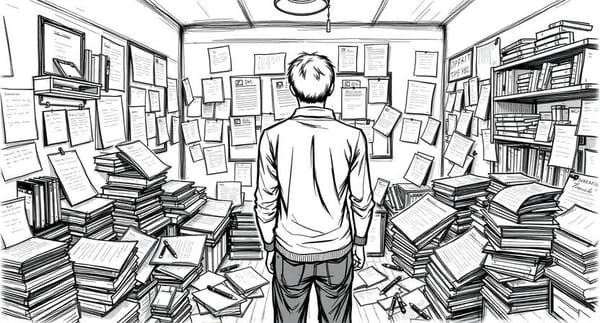

I began collating my experience in as much detail as possible. It took me months. There were so many contributing factors, I couldn’t create a comprehensible narrative—especially for non-experts—and I had to split it in two: One to describe the experience, the observed misconduct, the chronology of it all, and another for the subject-matter criticism. I also needed to know where to draw the line. What accusations were fair? Was there enough proof? What had priority? Where’s the line between error and misconduct?

There were plenty of challenges. For example, the most important thesis omitted so much, there was little evidence to attack. It still contained numerous flaws, but they weren’t obvious to untrained eyes. Understand their impact on final results took reflection, and in this confrontation I wasn’t the expert. I was out of my field, mentally wrecked, alone, running against decades of expertise firmly entrenched in a full professorship and all the support that entails. I was too easy to dismiss. If weight of word decided, I would lose. Unless I used theirs.

Since the flaws in the data concerned the field’s fundamentals, finding contradictions was easy—the publications themselves contained them. Their introductions detailed exactly how to ensure reliable data, and the subsequent results clearly diverge. Slowly, but surely, I gained a bit of confidence. My criticism was warranted, and they confirmed it. The insight soon fuelled obsession.

Beside a few habits that helped my recovery, I spent all energy on the project, frequently for ten hours straight. It was all I thought about. First thing in the morning, last thing at night. While I ate, while shopping. And the more I looked, the more I found. The theses slowly unraveled right in front of me. I don’t know how I ever carved a red thread through that mountain of information, but by the end I knew exactly what had happened.

I could prove the shown bits and pieces weren’t just exemplary plots to illustrate the procedure of analysis, but real measurements (thus annihilating the sole “argument” my supervisor had ever expressed). Multiple lines of reasoning fully discredited the data, at every shown processing step. Final results didn’t make sense. Controls were left out. One particular set of findings defied logic, even just in theory. Mountains of evidence were simply omitted, lacking even exemplary recordings. I could pinpoint not just the moment the problems arose, but what caused them, too. And I had corroborating statements by the original authors—for all of it: In their theses, their articles, their textbook.

The report took everything I had. I pushed myself hard, until I couldn’t focus any more, couldn’t sleep. I was dangerously close to collapse and I knew it. Whatever shape the report had, it would have to suffice; I had to get this over with.

Finally, sixteen months after dismissal, I submitted my indictment to the responsible academy of sciences' department for scientific integrity.