A glance at freedom

One of the coolest insights I've had since engaging with philosophy caused a shift in my understanding of liberty, perhaps the field's most central concept. Though we all know what it means, only few can explain it, and fewer still define it.

Historically, the word was intertwined with politics, with law: The ancient Greeks used the term to delineate the liberties granted by the state. Free was whoever was allowed to roam of their own volition, who was an equal amongst others—which did not at all entail the entire population. Since then, our understanding of freedom has quite significantly changed, a development kicked off by Plato, and a simple expansion of the term. Liberty, to him, was not just judicial, not just political. It was also about our inner selves, and the liberation from compulsions and desires; in short: from all exterior. To Plato, only the person who chose good, virtuous options over others, was truly free.

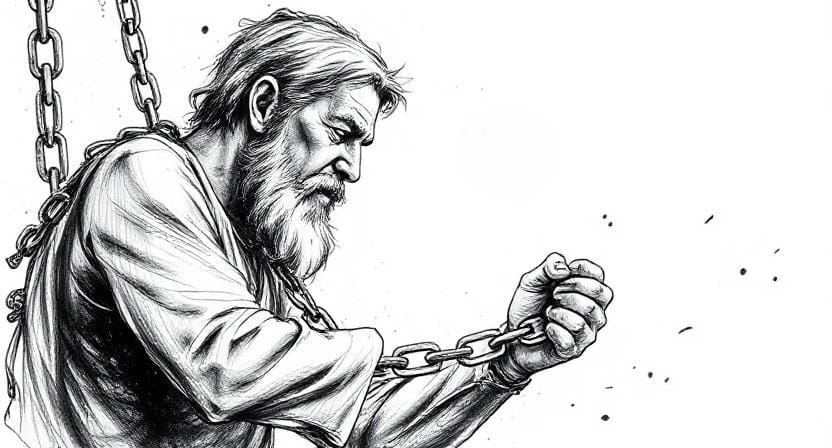

That focus on inner freedom grew ever more relevant, peaking, perhaps, in the Stoic view, which aimed to retain liberty in all circumstances. The stoics put reason above all else, arguing only the mind is truly under self-control, and thus the one thing that cannot be taken. Retain authority over thought, and you are always free. No matter how horrible your surroundings, you can always choose how you interpret them, and how you react. Stoicism thus finds a buffer between exterior and interior, and fills it with autonomous freedom. But one of the philosophy's other aspects undermines it: The stoics didn't just put reason at the top of their inner decision machinery, but above all else. They considered the entire universe the unfolding of an all-pervading logos, essentially nature's very own rationality—and if everything is an expression of such, it includes one's own reason. Subsequently, the most reasonable (and thus best) action is always submission to this logos. Ultimately, stoic freedom culminates in vanquishing desires and clearing the way for whatever will happen. It thus becomes withdrawal from giving any impulse. Which doesn't sound like freedom.

What's missing is active choice. The stoics might accomplish freedom from all exterior, but they are not yet free to decide on their own terms. Which is where things get interesting because it raises the question of what action to take, and that is deceptively difficult to answer (if one aims for freedom). Any choice necessarily entails the non-selection of all other possibilities, and thus reduces the realm of possibilities. It closes the door on many of the options available just a moment earlier. So then, does choice diminish freedom? Fortunately, it doesn't have to. Some decisions increase liberty. Oddly enough, they do so by submitting to boundaries—a realisation that requires a shift in perspective.

In one view, all available options are equal. They are simply possible reactions to the current situation, and without any goal, there is no reason for preference. With one, however, there is: Some choices will help approach the target, others less so. Apparently, we can group all possibilities by what outcome they provoke, and if that's the case, we can also find the line in between. If we then set liberty as our goal, it is intuitively easy to grasp what doesn't help us reach it: Anything that reduces our options (e.g. we can decide to never move again). In contrast, it is challenging to understand which choices increase possibilities; decisions that raise our competence, that lead to more options, that elevate our liberty. This qualified freedom (after Kant) is not so readily grasped because it reveals a seemingly paradoxical thing: We raise our liberty by voluntarily accepting constraints—to become proficient in a language (and open an entire world), we have to adhere to its rules. Were we to reject them, we would not increase our capabilities (as we would not be understood). In similar fashion, without a mutual understanding of possession (and our respect for it), ownership is impossible.

In short, we are only free as long as our freedom is not diminished by others, and thus only while we submit to a collectively accepted conduct. If we abandon these restrictions, our spheres of liberty will interfere, and ultimately, we will sacrifice liberty itself.

Freedom, thus, shapes its own horizon.